Africa’s Last Polar Bear: How Grief Took Wang After the Loss of His Lifelong Companion

When Wang, Africa’s last polar bear, passed away at the age of 28, it was not just the death of an animal—it was the quiet ending of a love story that had endured nearly three decades. His passing, confirmed on a Wednesday at Johannesburg Zoo, marked the end of an era and left behind a lingering ache for those who had watched him grow from a cub into a living symbol of devotion, resilience, and companionship.

Wang did not die suddenly. His body weakened slowly, but his spirit had begun to fade long before. For months, he grieved the loss of GeeBee—the polar bear who had been his companion since infancy, his constant presence, and the emotional center of his world.

A Bond That Defied Nature

In the wild, polar bears are solitary by nature. They roam vast Arctic landscapes alone, coming together only briefly for mating or maternal care. But Wang and GeeBee were different.

They arrived at Johannesburg Zoo as cubs, just six months old, and from the moment they were introduced, they became inseparable. For 28 years, they lived side by side—eating together, resting together, swimming together. Zoo staff and visitors alike often remarked that where one was found, the other was never far away.

Their bond was rare. Extraordinary. Almost human in its depth.

To generations of visitors, Wang and GeeBee were not just animals in an enclosure. They were a pair—a living reminder that emotional connection is not exclusive to humans.

The Day Everything Changed

In January, GeeBee died suddenly from a heart attack.

For Wang, the loss was devastating.

Almost immediately, his behavior changed. The polar bear who once swam endlessly and responded eagerly to enrichment activities became withdrawn. He wandered aimlessly, pacing without purpose. He stopped swimming—an activity that had once brought him obvious joy. His appetite declined. His eyes, once alert and curious, dulled with confusion and sorrow.

Zoo staff recognized the signs of grief.

They tried everything.

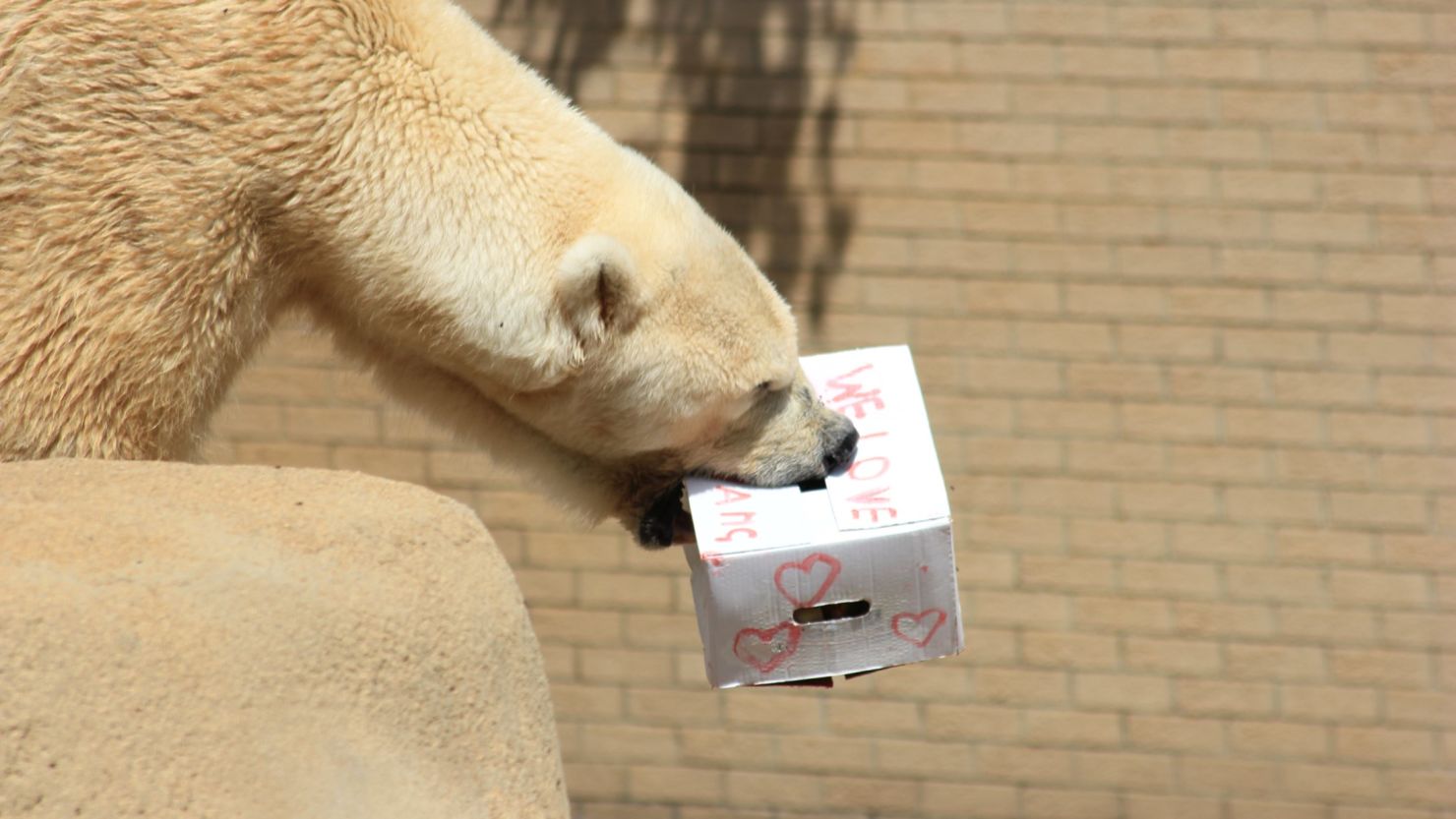

Special treats were offered. Favorite toys were introduced. Caretakers spent extra time with him, speaking softly, offering reassurance. On Valentine’s Day, Wang received a carefully prepared gift—a box filled with fruit and meat, decorated with hearts and a note that read: “We Love You, Wang.”

But love, as powerful as it is, could not replace the companion he had lost.

A Body Worn Down by Time and Loss

As Wang’s emotional state declined, his physical health followed. He had long suffered from chronic arthritis, a painful condition made worse by age. Liver failure soon compounded his suffering, and despite ongoing veterinary care, his condition worsened steadily.

The zoo’s chief veterinarian described the final decision as “heartbreaking but necessary.”

After careful evaluation, the team concluded that Wang’s quality of life had diminished beyond recovery. Continuing treatment would only prolong his pain.

And so, with heavy hearts, they made the compassionate choice to euthanize him.

Wang passed away peacefully—but not without meaning.

A Life Lived Far From Home

Wang’s story began far from Africa.

He was born in a zoo in Japan and later transferred to Johannesburg as part of an unusual polar bear–lion exchange program. GeeBee, born in Canada, joined him in 1986. Together, they adapted to a climate vastly different from the icy Arctic landscapes their species evolved to inhabit.

Against all odds, Wang lived to 28—well beyond the average lifespan of wild polar bears, which typically do not exceed 20 years. According to Agnes Maluleke, carnivore curator at Johannesburg Zoo, his longevity was a testament to the care he received.

Yet his life also raised difficult questions.

Polar bears are animals of snow, ice, and vast frozen seas. Living in Johannesburg’s warm climate required constant management and careful environmental control. Despite the zoo’s best efforts, some aspects of a polar bear’s natural life can never truly be replicated.

Wang and GeeBee never bred—a fact attributed to the absence of cold conditions necessary for polar bear reproduction.

The End of an Era

With Wang’s passing, Johannesburg Zoo announced that it has no plans to replace its polar bears. The chapter has closed.

Visitors who once gathered to watch the iconic duo swim and rest together now face an empty enclosure—and an absence that feels larger than space alone.

Wang was not just Africa’s last polar bear. He was a reminder of what animals feel, what they lose, and how deeply they can love.

What Wang Leaves Behind

Wang’s story forces us to confront uncomfortable truths.

Animals in captivity do not merely exist—they experience. They form bonds. They grieve. They suffer loss in ways that mirror our own. Wang did not simply age into death; he mourned his way there.

His decline after GeeBee’s passing stands as powerful evidence that emotional well-being is inseparable from physical health.

And his life raises urgent ethical questions about conservation, captivity, and responsibility.

Are zoos sanctuaries—or compromises?

Can love and care fully replace natural habitats?

What do we owe the animals we choose to protect?

A Legacy of Love and Warning

Wang and GeeBee’s bond defied biology, geography, and expectation. Together, they showed millions of people that connection does not belong to one species alone.

Wang’s death is heartbreaking—but it is also instructive.

It reminds us that protecting polar bears means more than keeping them alive. It means preserving the Arctic ecosystems they depend on. It means addressing climate change, habitat loss, and human impact before stories like Wang’s become even rarer—and then impossible.

In the end, Africa’s last polar bear leaves behind no cubs, no lineage.

But he leaves behind something else.

A story of loyalty.

A story of grief.

A story that asks us to look more closely at the lives we hold in our care.

And perhaps—if we listen carefully—a call to do better.