The Stolen Children of Guatemala: A Story of War, Adoption, and Resilience

From the 1960s onward, amid the turmoil of Guatemala’s long and bloody civil war, a chilling pattern began to emerge — children were vanishing. They were stolen, sold, or deceitfully taken from their mothers by jaladoras — local child brokers who preyed on poverty and chaos. Many of these children ended up in the arms of foreign families, their stories rewritten, their identities erased. What the world saw as “international adoption” often hid the deep scars of war crimes.

Dolores Preat (name changed for privacy) is one of those stolen children. Her journey to uncover the truth began in 2009. Adopted by a Belgian family at the age of five in 1984, her adoption papers listed her mother as Rosario Colop Chim — a woman from the highlands ravaged by Guatemala’s internal conflict between 1960 and 1996.

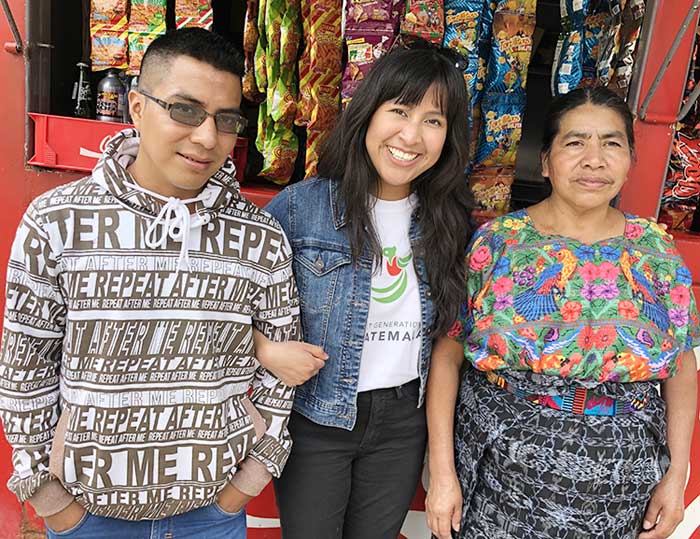

Armed with a few Spanish phrases and no knowledge of her native K’iche’ language, Preat flew back to Guatemala. Her search led her to Zunil, a small town at the foot of a volcano, whose name in K’iche’ means “reed.” The town is predominantly inhabited by Indigenous Maya families, where memories of the war still linger in whispers and silence.

When Preat reached Colop Chim’s house, she was met by the woman’s sister, who was visibly shaken. “Rosario never adopted a child,” she said quietly. “That little girl was taken.”

Following the clues, Preat met another woman — someone her own age, with strikingly familiar features. The woman burst into tears as she called her mother and told her story. Later, DNA testing confirmed the unimaginable: Rosario Colop Chim was not Preat’s biological mother but her kidnapper. The woman Preat had met was her biological sister. Their real mother had spent decades mourning the baby stolen from her arms.

The truth was almost too painful to bear. Colop Chim had kidnapped the child of her neighbor, then forged adoption documents claiming to be the mother. She worked as a jaladora — one of many women hired by lawyers to procure babies for foreign families desperate to adopt. These adoptions often bypassed the legal requirement of parental consent, replaced instead by forged signatures and fabricated stories.

After the kidnapping, Preat’s real parents searched everywhere — from hospitals to nearby villages — terrified but determined. They never went to the police; Colop Chim had threatened to kill them if they spoke. At that time, Guatemala was gripped by state violence. More than 200,000 civilians, mostly Indigenous Maya, were killed by government forces and paramilitary groups. Hundreds of kidnapped children disappeared into the international adoption system.

In 2015, six years after reuniting with her biological family, Preat filed a criminal case against Colop Chim. Her lawyer argued it was not just a kidnapping, but a case of forced disappearance — a crime under Latin American human rights law. The court agreed that the crime was ongoing, as the victim’s true identity had been suppressed for decades. Colop Chim was sentenced to 15 years in prison.

But Dolores Preat’s case was not unique. She is one of roughly 40,000 Guatemalan children adopted abroad — most to the United States, Canada, and Europe. The first wave of international adoptions began in the late 1960s, peaking in the 1980s. What started as humanitarian aid soon became an unregulated industry.

Private adoptions became especially lucrative. Lawyers in Guatemala partnered with international agencies, charging between $3,500 per child in the 1970s to as much as $45,000 in later years. For families in the West, private adoption was faster and “more flexible.” For the brokers, it was a business — one that thrived on desperation.

Jaladoras were tasked with finding infants, convincing mothers to give up their babies, or even registering unborn children for future adoption. In many hospitals, especially in rural areas, women were told their babies had died shortly after birth — only for those newborns to reappear months later in adoption paperwork overseas.

The United States was aware of adoption fraud as early as the 1980s and began requiring biological mothers to appear for interviews at the U.S. Embassy. However, language barriers and unreliable translators made it difficult to confirm genuine consent. Despite the concerns, the number of Guatemalan adoptions to the U.S. soared — 29,807 Guatemalan children were adopted by American families after 1990.

While cases like Preat’s are rare, they expose a deeply flawed system — one where bureaucracy, profit, and power often outweighed the rights of children and parents. Investigations have since revealed the involvement of lawyers, government officials, and even military officers in illegal adoption networks.

Dolores Preat’s story is more than a tragedy — it is a reminder of resilience and truth. It tells us that even in the face of war, fear, and corruption, the search for one’s identity is unstoppable. The little girl stolen decades ago grew into a woman who refused to live a lie.

Her journey home was not only a reunion with her family but also a restoration of justice — a voice for thousands of stolen children still lost in the paperwork of history.