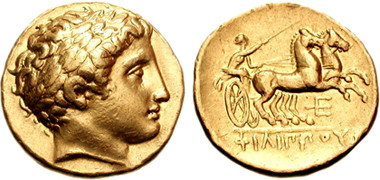

Ancient Greek Stater Coin, 323–315 BC

The military triumph of King Philip II of Macedon over the Athenians and Thebans at Chaeronea in 338 BC established Macedonian supremacy across Greece and paved the way for the vast empire his son, Alexander the Great (reigned 336–323 BC), would soon win from the Persians.

Yet during his lifetime, Philip had other achievements of which he was equally proud—among them, his victories at the Olympic Games. In 352 BC, he won the tethrippon, the four-horse chariot race, followed by another triumph in 348 BC in the synoris, the two-horse chariot race. Earlier, in 356 BC, he had also taken first place in the horse race. These prestigious victories inspired Philip to issue coins celebrating his success, and this gold stater depicts the two-horse chariot from his synoris victory of 348 BC.

On the reverse, the coin shows a chariot racing to the right, driven by a charioteer within the border, his whip raised as the horses gallop toward the finish line. Above the scene is a faintly visible victory wreath, signifying its Olympic glory. Beneath the ground line, in the exergue, appears the inscription “Philip,” along with a serpent and the monogram Α and Π, marking its mint—likely Pella, the Macedonian capital. The obverse features the laureate head of Apollo, the quintessential Greek god of light, music, and prophecy.

Though this coin type originated under Philip II, it continued to be struck posthumously, including during the reign of Philip III Arrhidaeus (323–317 BC). Such continuity made practical sense, as these coins were well known and trusted across regions—even reaching northern Europe, where Celtic tribes imitated the design for centuries.

Beyond economic stability, the coin also served as powerful propaganda: it celebrated Philip’s Olympic triumphs, reinforcing his image as a ruler favored by the gods and destined for greatness. As Plutarch (in Alexander 4) noted, Philip personally oversaw the designs of his coinage. This enduring coin thus stands not only as currency but as a symbol of how athletic glory and political ambition worked together to shape Philip II’s—and later Alexander’s—imperial legacy.